A new study published in Nature on 6th June reveals that on a global scale Hurricanes, or to be a tad more precise, Tropical Cyclones, are slowing down. That sounds good, but in fact it is quite the opposite and is very bad for those under the path of a Hurricane that is moving more slowly.

What does the paper reveal?

Titled “A global slowdown of tropical-cyclone translation speed“, it reveals that the tropical-cyclone translation speed has decreased globally by 10 per cent over the period 1949–2016.

This is not a paper about the intensity of Hurricanes and so it is not suggesting that the strength of the wind that blows when a Hurricane develops is not as strong as it use to be. Instead it is looking at how fast the Hurricanes system moves over sea and land. Due to global warming the actual intensity is increasing and so they are becoming more severe.

So what is the paper about?

As the atmosphere warms the global circulation system changes. There is evidence that global warming causes the summertime tropical circulation to slow down. Because this is what moves these tropical cyclones across the sea and land, they move more slowly.

There is also one other rather important factor. Because of the increased heat, both the intensity and also the amount of moisture in the storm system increases. The amount of rain that any one area will experience is proportional to both the translation speed and also the amount of water-vapour that the storm system carries. Net effect: Warming leads to a great deal more rain.

The magnitude of the slowdown varies substantially by region and by latitude, but is generally consistent with expected changes in atmospheric circulation forced by anthropogenic emissions. Of particular importance is the slowdown of 30 per cent and 20 per cent over land areas affected by western North Pacific and North Atlantic tropical cyclones, respectively, and the slowdown of 19 per cent over land areas in the Australian region. The unprecedented rainfall totals associated with the ‘stall’ of Hurricane Harvey13,14,15 over Texas in 2017 provide a notable example of the relationship between regional rainfall amounts and tropical-cyclone translation speed.

Key Message

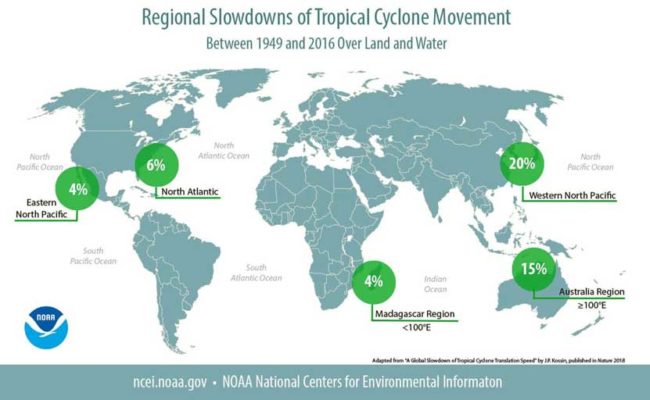

The percentages within the following diagram show how much tropical cyclones have slowed in those regions in the past 70 years. Local tropical cyclone rainfall totals would be expected to increase by the same percentage because of the slowing alone. Increases in rainfall because of warming global temperatures would compound these local rainfall totals even further.

Criticism

From here …

Is it really Climate Change?

First, he noted that over the more than 60-year period of the study, there may be natural, decades-long cycles in the climate system that could affect the steering of storms and have little or nothing to do with global warming. So it is not clear just how much of the change Kossin found is attributable to human-induced climate change.

Kossin would agree on that point.

“My study is pretty far from an attribution study,” he said. “I’m finding something that might be considered consistent [with climate change], but, really, no idea what’s contributing what to this signal. At least not yet.”

This is a very good positioning of it all. We should only go as far as the data enables us to go, and no further.

How complete is the data?

Zarzycki’s second point is that our means of studying hurricanes have also changed. Indeed, after about 1980, we could observe them by geostationary satellite — before that, storms in the open ocean might have been missed completely and gone unrecorded, at least if they never encountered any vessel.

That means storms farther from land in the earlier part of the study may not have had their speeds included in the study.

Kossin, in his paper, writes that he would not expect big changes in his results as a result of different means of measurement, since “estimates of tropical-cyclone position should be comparatively insensitive to such changes.”

Bottom Line

What we can’t avoid here is that in a warming world, the intense, torrential rainfall that Tropical Cyclones bring is getting more intense.

“Inland flooding, freshwater flooding, is taking over as the key mortality risk now associated with these storms,” Kossin said. “There’s been a sea change there in terms of what’s dangerous. And, unfortunately, this signal would point to more freshwater flooding.”

Press Release

The University of Wisconsin-Madison has issued a press release regarding the publication of this study. This enables us to gather up a couple of further insights from the author of the study, James Kossin.

“Just a 10 percent slowdown in hurricane translational speed can double the increase in rainfall totals caused by 1 degree Celsius of global warming,”

“The rainfalls associated with the ‘stall’ of 2017’s Hurricane Harvey in the Houston, Texas, area provided a dramatic example of the relationship between regional rainfall amounts and hurricane translation speeds,” says Kossin. “In addition to other factors affecting hurricanes, like intensification and poleward migration, these slowdowns are likely to make future storms more dangerous and costly.”

Further Reading

- The published study in Nature (sorry, they have a paywall)

- The Press Release

- Chris Mooney writes about it all in the Washington Post